This week on LinkedIn:

Jeff Bezos on ‘when the data and the anecdotes disagree, the anecdotes are usually right’

The economics of a free Baby Guinness for a five start review

And now onto this week’s CX Story…

We do understand that paying more money for something is never pleasant. However, you don't necessarily need to be okay with that. You're welcome to cancel your subscription at any time

I’ve been a user of Evernote - the online note taking app - for well over a decade. It’s my home for everything I think might come in useful in the future: interesting articles; ideas for CX Story posts; notes on funny things I’ve seen whilst commuting which will form the basis of my smash hit BBC2 SitCom due to hit the screens sometime in 2029.

Given I’ve been with them for so long, I thought they might be keen to keep me as a customer. But it turns out, they weren’t. And it seems a lot of other companies might be taking their customers’ decisions for granted, too.

As important as Evernote is in my life (or ‘workflow’, as I’m told I’ supposed to call it), I was a bit taken aback when I noticed the annual price jumping up a hefty 150%, with no prior warning, no obvious explanation. Being me, I got in touch with them to find out if this was some kind of mistake, and why I hadn’t been told about it before.

Whilst the first part was sort-of answered, the second was ignored. Reading down, I realised why.

So, reply I did. And a few days later, I was longing for the safety of the overly-polite AI bot:

At no point had I said I wanted to cancel, or even that I thought the price was outlandish. All I’d really asked was to understand why I hadn’t been told in advance, and whether the change in price opened up any more benefits to me. But email after email, the message was clear: if you don’t like it, go elsewhere.

In some ways, I understand this reaction. The deterioration in customer and company relationships has led to this kind of fractious reply, with frontline teams left to be the battering ram for decisions made in other parts of the organisation.

But to simply open the door for customers when they may be on their way out is commercial madness - especially as the best time to deepen the relationship with customers is at these fracture points, and the time to be at your best is when they have the choice to leave.

Take this letter from my Home Insurer, on noticing I hadn’t renewed my payment with them for another year. Hardly the most compelling reason to stay, is it?

Or this, from my Broadband provider when I asked if I was out of contract. No hint of ‘and we have some great deals you might like, we’d love you to stay as our customer!’

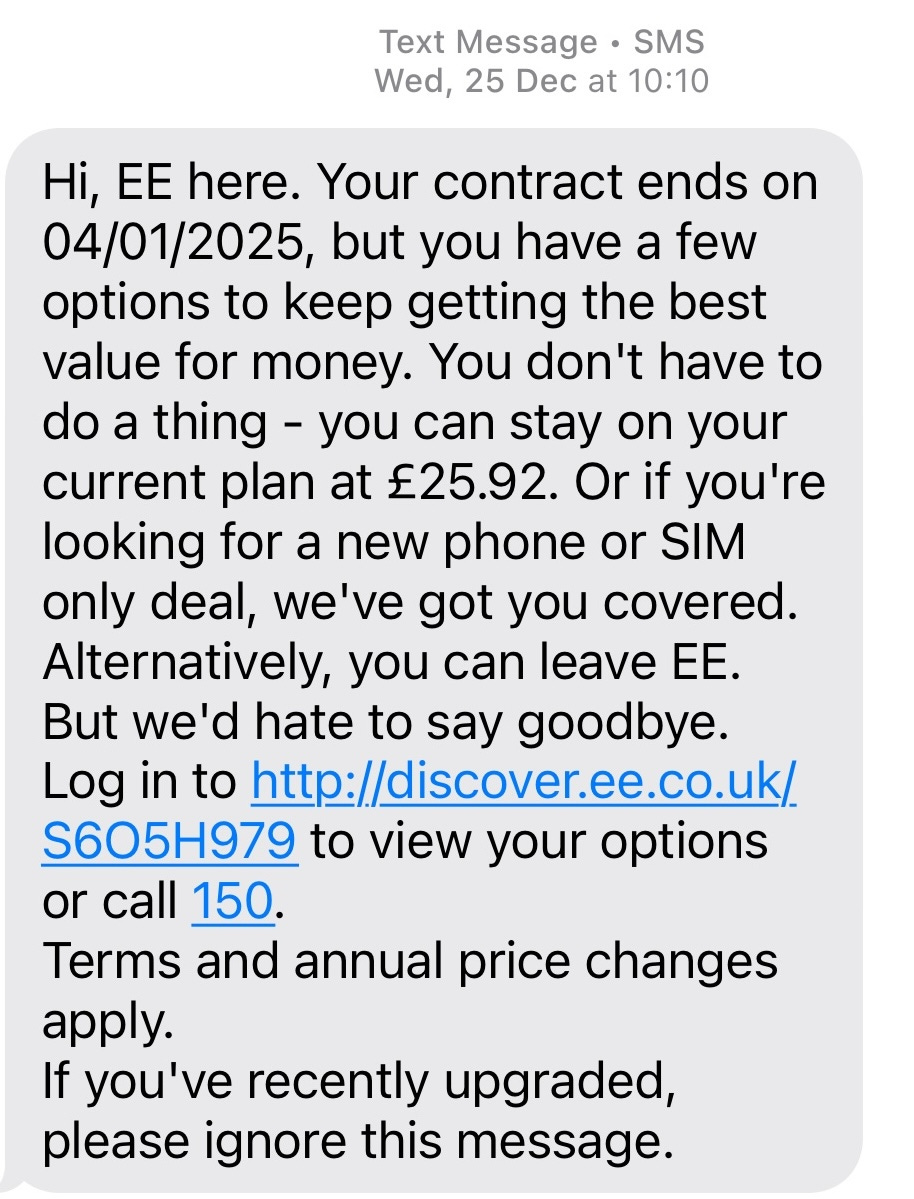

This isn’t hard to do. When my contract came up with EE recently, I got this text message - on Christmas Day no less - telling me I was free to go, but saying they’d really like me to stay. So, of course, they become my first option to look at. And stay I did.

This may be a symptom of apathy, of having to deal with difficult and angry customers every day. Or, as my futurist friend

suggested to me, it’s could be a sign of abundance, a lack of needing to try.But what I do know is that, as Joe MacLoed speaks so eloquently about, we are really bad at endings, focussing on the functional tasks over the emotional feeling. This is as true with customer experience as it is for colleagues leaving a business - take this LinkedIn post about a social worker deciding to leave the profession after twenty years, and the letter she got in response.

Ultimately, organisations only get revenue from earning customers’ decisions in their favour, not from their products and services alone. And the easiest decisions to win are when those customers are already with you. Otherwise, you just have to win them all over again.

*I should say that Evernote did end up providing a full and fantastic reply, and I’ll be staying with them for a while more.