When you come home from India and spend the next few days throwing up, people presume they know what’s caused it.

‘Couldn’t handle the spice?’

‘Tummy had trouble with the water?’

‘I bet you got it from having ice in your whisky’

These are all possibilities, except the last one. Whilst I almost exclusively drink water and whisky, I never mix the two.

I was sure it was the plane food. I remember thinking at the time that it looked bad. Reheated rice and chicken, sat on a plane for several hours before serving. A recipe for culinary and gastronomic disaster.

So me being me, I complained. The complaint system was surprisingly easy, even having a telling ‘I got food poisoning from the plane’ as one of the default complaint options.

And then, I waited.

Many years ago, consultancy firm Vanguard coined the phrase ‘Failure Demand’, to describe the costs associated with not getting something right the first time

‘Failure Demand is ‘a demand caused by a failure to do something or to do something right for the customers’

Failure to do something - a failure to turn up, call back, deliver something - that causes the customer to make another demand on the system.

I think you can add something else to this list. A failure to answer the next question. The question that you know, as an organisation that has dealt with an issue many times, the customer will ask. In fact, you’ll know the answer to the question before the customer realises there’s even a question to ask

So I make my complaint to the airline, and then hear nothing. For two months. Onto Twitter I go.

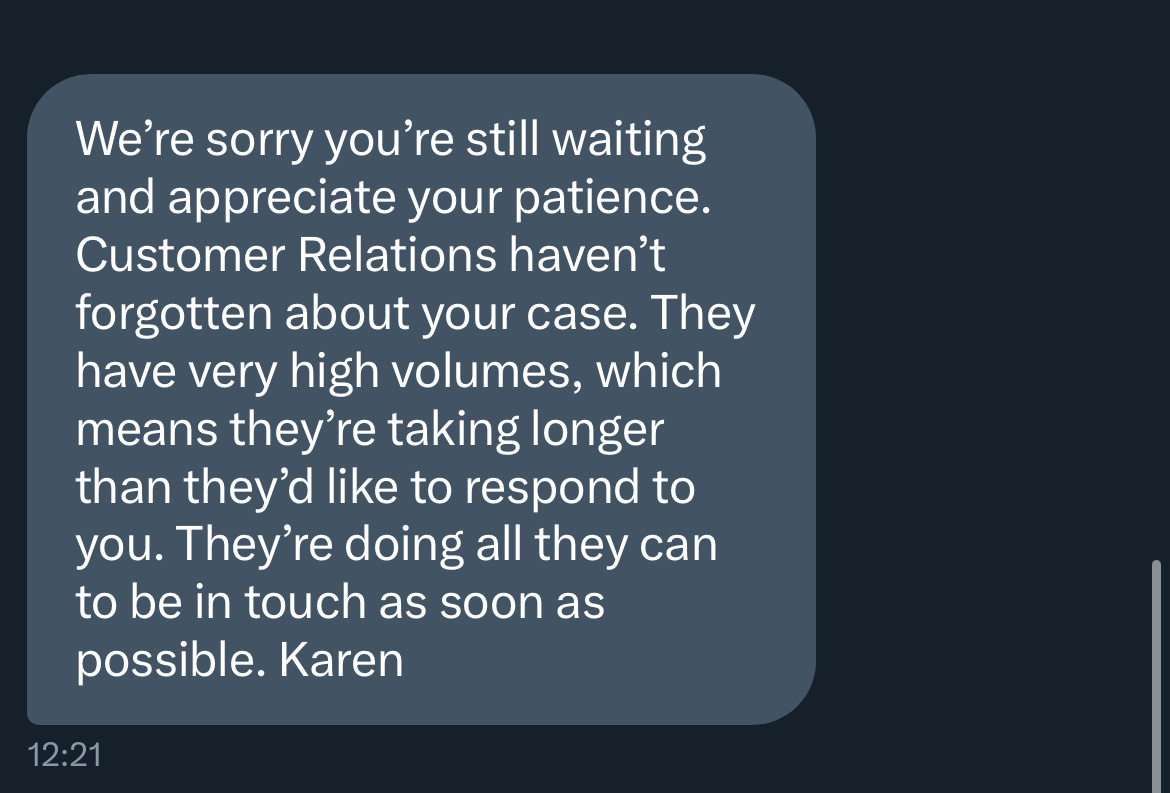

And in fairness, received an immediate reply:

And then the now traditional:

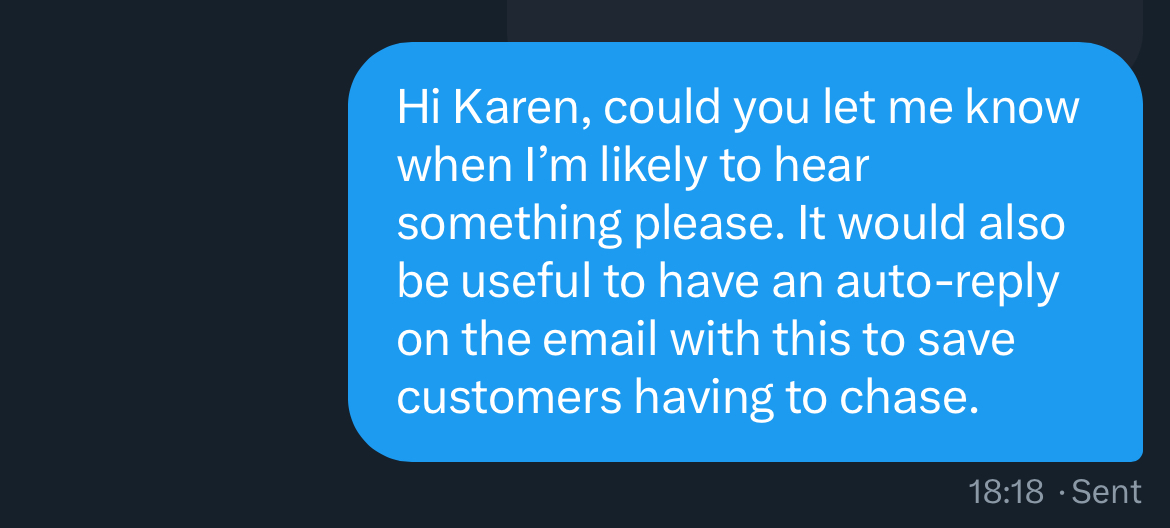

But we all know what my next question is:

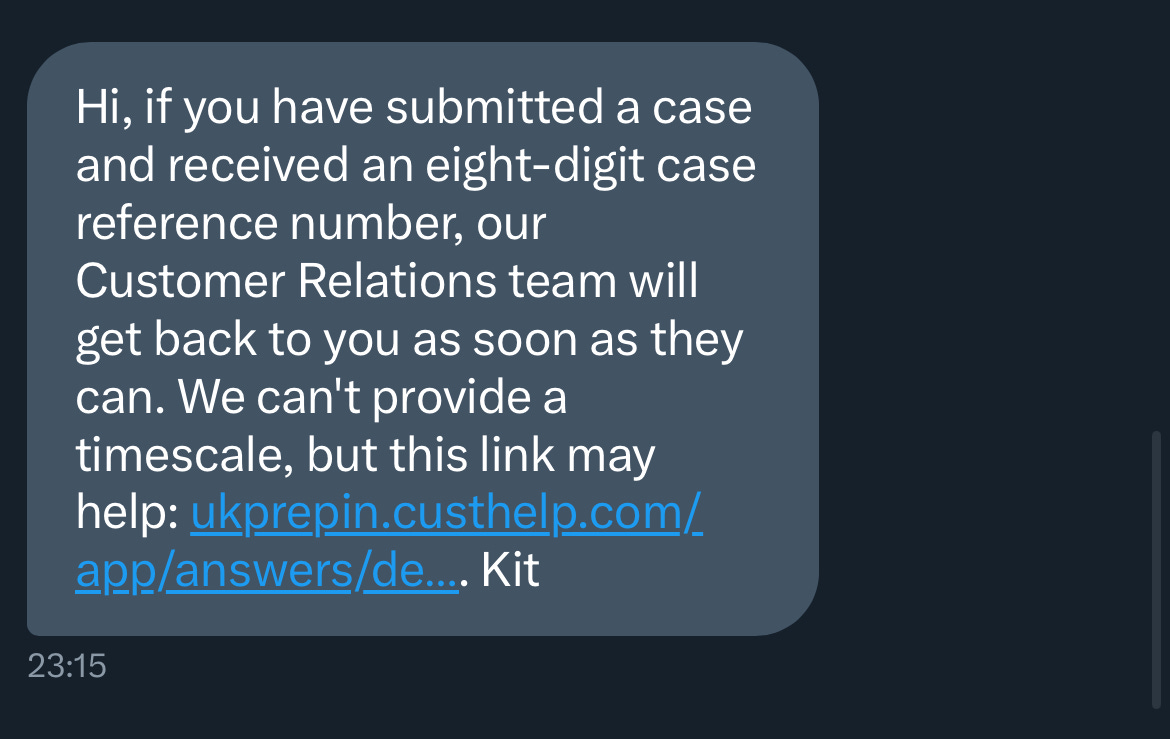

This time, the reply is slightly more helpful, with a link to the case management system:

So I follow the link, hoping to get an update. And:

The initial complaint system. The confirmation email. The initial message. The subsequent message. The Case Status page.

All opportunities to answer the one question I have: ‘When is this going to be resolved?’. All failing to answer that question, meaning I get in touch again, and again, and again.

All that’s needed is to answer the customer’s questions before they ask it, to set expectations of what’s going to happen and when.

Firstly, when the customer gets in touch and they reply, let me know how long it’s likely to take (with a link to the case management system, in this case)

Then, as it gets closer to that time, if they’re going to miss the deadline, send an automated email explaining that, setting a new expectation of timescale.

Finally, on the case management system, they could have more of a timeline, a progress bar that shows where the complaint is up to in its journey to being resolved.

All of these and inexpensive to do. Especially because - for an organisation that claims it is dealing with ‘very high volumes’ - it would dramatically reduce the number of customers getting in touch with questions in the first place, giving them extra resource to divert to, oh I don’t know, dealing with (alleged) food poisoning complaints.

But yet this often doesn’t happen. Because the costs to invest in a better system, and the costs for dealing with customer queries, sit on two different parts of the balance sheet, under two different senior managers, so the costs are often not seen as part of the same thing.

Organisations know what customers will want to know, they have the power to read their minds. More time spent planning, predicting and answering in advance will help give customers a much better experience. And it’ll save the organisation a fair amount of money, too.