In Defence of NPS 📈

Or how to make surveys less painful and more useful

If you’ve read my book (I’ve barely mentioned it…), you’ll know I’m not the biggest fan of feedback surveys. So, it’s not a surprise that people often take that to mean I really dislike NPS.

Which I do! It’s a waste of customer’s time, a huge resource drain in organisations, and an excuse to avoid spending real time with real people. It’s also a hypothetical question when you could just ask people if they will actually recommend you (or see if they have).

But, if I’m to be a little more fair and a little less click-baity, it’s not really NPS that’s the issue, but the way NPS-type surveys and measures are used in organisations. So in my defence of NPS, there’s five things that organisations need to do to make it, and other similar measures, work really well:

1) Prioritise what you need to know

Too many satisfaction surveys ask for a customer’s opinion on performance against a generic framework or a set of cross-industry ‘Customer Experience Standards’, on absolutely every transaction. That’s not hugely helpful, unless you’re satisfied with staying in the middle of the pack, or happy to drown in data.

Every organisation is different, with different strengths to build on, different strategic aims, and different plans for the future. So customer experience measures need to be focussed on the customer experience you’re trying to create - the specific vision and promises you’re making to your customers - not a bland measure of performance that keeps you in the middle of the crop.

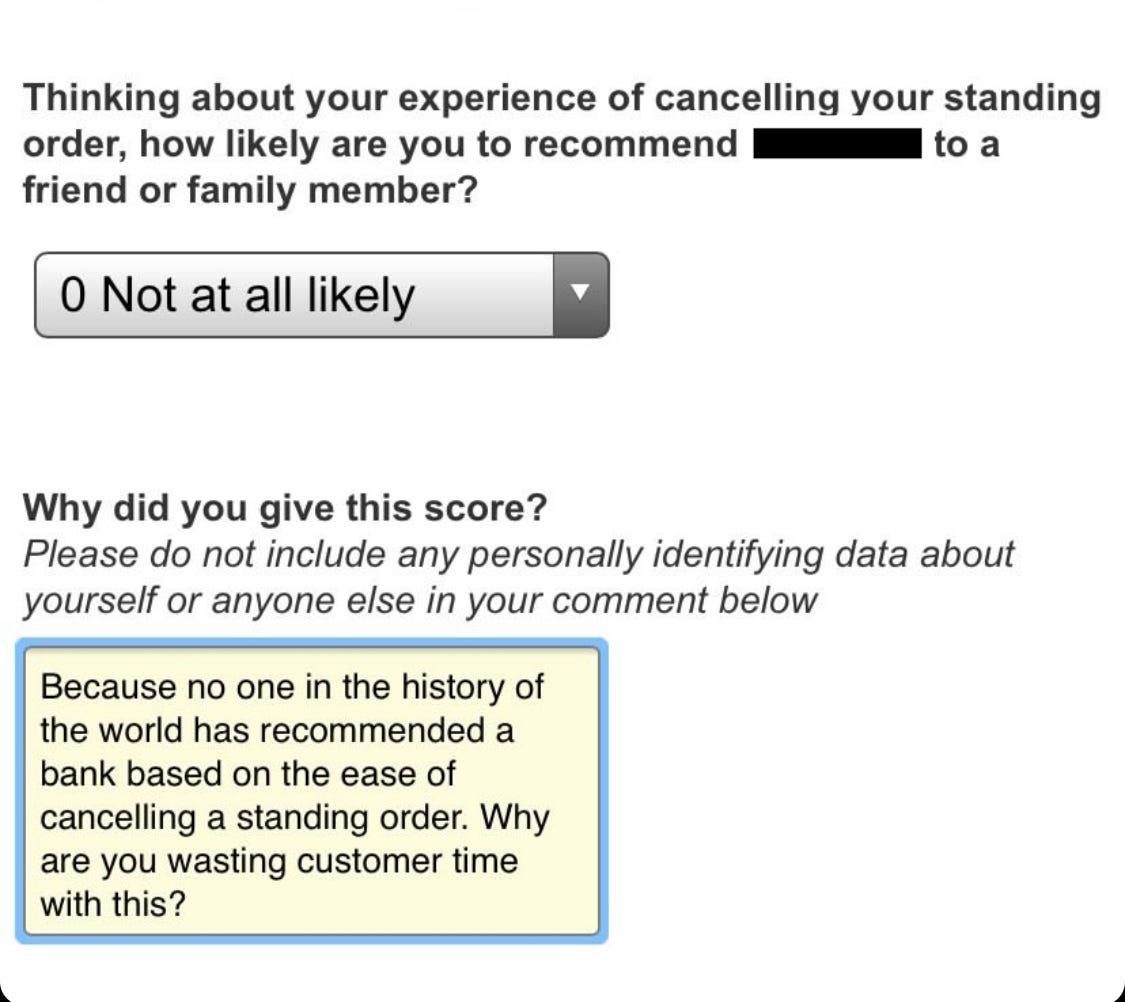

2) Only ask when you have to

The main rule of any satisfaction survey should be that you only bother the customer when it’s absolutely necessary. Too frequently, these surveys are used as an outsourcing of responsibility from the organisation to the customer, asking for feedback on every transaction. This is bad for the customer, but it’s bad for the business too.

Firstly, it’s means customers are less likely to pay attention to an organisation’s communication, as 90% of what they receive is asking them to do something, rather than being genuinely useful. Secondly, it’s creates a deluge of information into a business, often too much to handle or process in a helpful way, requiring teams of people to manage the data.

Customers should only be asked for their opinions once every other data source has been exhausted. This includes behavioural data, complaint data, completion rates, drop outs rates, and crucially, frontline colleague feedback. Doing this helps create a hypothesis for the areas you need to know about most, and makes the contact with customers less frequent and more valuable.

3) Focus on actuals, not averages

An ex-economist I worked with used to say:

‘If your head is in the oven and your feet are in the freezer, on average your temperature is fine. But you’re dead.’

In weekly management meetings around the world, you’ll hear discussions on average waiting time, average satisfaction, average performance across departments. Yet this style of measurement hides the true impact being felt by customers.

Isn’t it more useful to focus on the 10% of customers who waited more than 30 minutes? What happened there? How do we fix that? And what about the 10% of people who gave us 10 out of 10? Let’s celebrate that! Then look at what we can learn, and how we can replicate that.

You can go further, and change your measure into something that focusses on customer outcomes, not the measure itself. Why not measure ‘Human Lives Wasted’ instead of ‘Average Waiting Time’? ‘Relationships Started’ rather than ‘Accounts Opened’? ‘Customer Holidays’ instead of ‘Savings Balances Held’? Measuring actuals rather than averages may bring the human impact to life.

4) Make it part of a broader suite

The danger of satisfaction surveys is that all this customer data coming into organisations convinces leaders that they’re close to what matters to their customers, whereas in truth, they’re simply close to customers’ opinions of their business. It’s a very subtle, but very significant difference.

To really understand what matters to customers, you need to have an insight approach that looks at three areas: Their real life, the things that matter to them most; their relationships with organisations and the services they use to help; their transactions with you, and how easy and enjoyable you are to be a customer of.

5) Say thank you

A few years ago, Riverford asked me for my feedback. I happily gave it, as they barely ever ask, and I really like being a customer. A month later, they emailed again, thanking me for the feedback, sharing what they’d heard from customers, and telling me what they were going to do about it. A classic ‘You Said, We Did’.

Firstly, it makes me feel listened to as a customer, rather than thinking my feedback (which I’ve given up my time to share) is disappearing into a black hole. Secondly, it makes it more likely I’ll share feedback again, knowing they’re doing something with it. And getting me to fill in a survey is no easy feat.

Understanding your customers is crucial to creating and sustaining a commercially successful, customer-led business. Doing it in a way that respects your customers’ time and effort is even more so.