Enemy in Paris: The impossibility of the French Metro system (and why you still need humans to help)

The one where I get trapped in France

Impossibilité pour les voyageurs de prendre les tickets sur le téléphone

Sometimes, you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone. And that’s exactly how I felt about Transport for London, as I was stood on a platform in Paris’ Gare du Nord station, with three suspicious ticket inspectors, trying to work out how to buy a ticket to the airport.

I love TfL. I love how complex it is, how messy it is, what a challenge it must be to move eight million people every day around the greatest city in the world. And after a week in another of Europe’s historic capitals, I absolutely love the fact you can just use your credit card to make contactless payments.

Naively, I’d presumed this would be the same in Paris. Not so.

First, I had to buy a digital ‘Oyster’ card for me and the family - four separate cards, all on one phone.

Tap and go? Tap and no. Every trip required buying a new ticket in advance for each journey (we weren’t doing enough for Travelcards), every trip required a tap in and tap out.

On the first day, I was getting nowhere. Card one was fine, the others less so. No-one around to help, just a gate and an intercom, with me on one side, the the kids on the other.

I buzz. I wait. Someone answers, someone hangs up. I try again, and again. Same difference.

Eventually, I work out card one has automatically set to ‘Express Mode’, meaning whenever I touch my phone to the gate, that one gets priority. Neat feature - but not if you have more than one card on your phone.

Fast forward to the end of the week, and I’ve mastered the system. One trip left, from Porte Maillot to Charles De Gaulle Airport.

We march (read: I march the family) to the station, lug the suitcases down the stairs (the escalator only goes up), and get out my phone to buy the tickets and scan us through. But the ticket I need isn’t available.

It’s fine, there’s a machine, we’ll get paper tickets.

We won’t get paper tickets. No-longer sold from this machine. Top-ups only.

That’s fine, we’ll top-up the cards.

We won’t top up the cards. Only physical cards can be topped up from the machine, no phone passes.

So, I press the intercom, and I wait. They answer:

Hi, do you speak English?

No, I don’t speak any English I’m afraid

(he says, in perfect English)

I’ll get my colleague who can speak English much better than I can

I wait. They hang up.

So, I panic. We have a plane to catch. I buy any ticket that will get us through the gate and onto the train.

Which brings me to the platform in the Gare du Nord. Being a good, upstanding citizen - and anticipating not being able to get out at the other end - I went to ask three ticket inspectors how to get the right ticket.

A five minute discussion ensued as they played with the app and searched the web, until eventually they agreed it was impossible, and they’d have to sell me a ticket instead.

As this was just a flimsy piece of paper, I asked the obvious question:

How will I get out at the other side?

Oh, just show this to one of the colleagues there

Reader, I think you know what happened.

We got to the airport. We got to the gate. There were no colleagues. But there were a lot of people - twenty or more - all stuck on the wrong side of the barrier. And there was an intercom.

We buzz. We wait. Someone answers, someone hangs up. We try again, and again. Same difference.

Eventually, someone with an unidentifiable job, but who has a pass to open the gates, walks past and is descended upon. With no questions asked, he just opens the gate for every single person waiting to get through, then goes on his way.

Now let’s be clear. There’s a chance that throughout this experience, there were mistakes I was making that might have made it all work better (including not speaking French).

But two things stand out to me.

The first is that, if your customer makes a mistake, it’s your fault for it being possible for the customer to make a mistake.

And the second is, because of that - as I wrote about in The Problem Problem and If the Schuh Fits - you simply have to be there to help if something goes wrong, because you have to presume there will be problems.

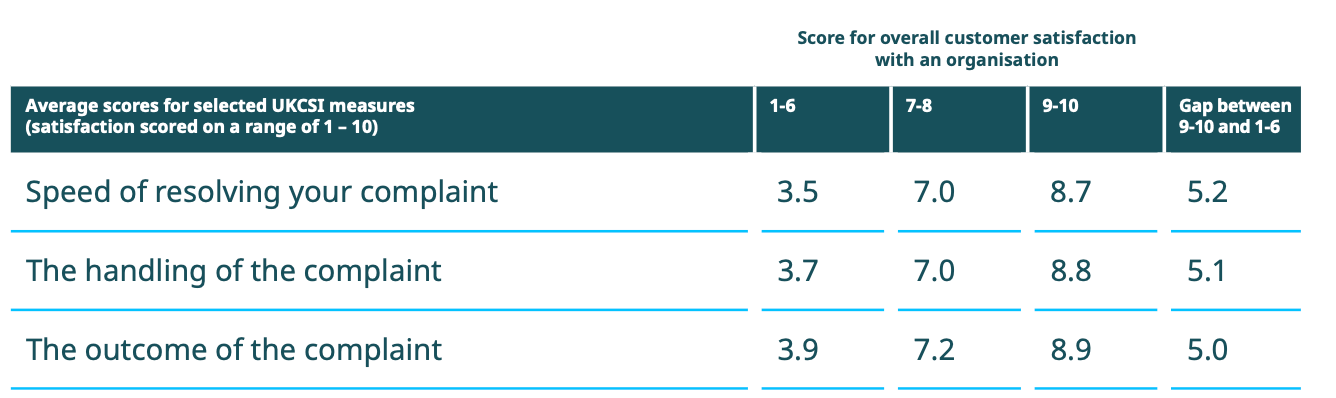

As the Institute of Customer Service showed recently, the ability to handle issues well is still the defining gap between organisations with poorly or well perceived experiences.

And as more of our experiences become automated with the advent of Artificial Intelligence, the temptation for companies to trust the processes and presume no faults is a great one - but it’s one that could leave your customers locked outside.